During my writing retreat in Jaén last week, I signed up for a tour of the three cultures of the city―Christian, Muslim, and Jewish―but nobody else registered. The guide cancelled it. I wanted to see the remnants of the Moorish that existed between 711 and 1492 A.D. and the Jewish community that mostly thrived there from 611 to 1492. In that fateful year, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella ordered Jews and Muslims expelled from the country. They decreed to stamp out heresy and investigate and eliminate followers of these faiths, even those who had converted to Christianity. I wanted to know what went on in the buried part of the city, not Saint Catherine’s Castle or the Cathedral of the Assumption which towered over everything else. Like other cities in the southern region of Andalucia, rich and convivial Jewish, Moorish, and Christian cultures co-existed for a while. Today, the remains blend into the modern city. I plugged my destinations into Google Maps to find my way to the past.

Given my proclivity to wander in the opposite direction even with a map, I headed for the most obvious and visible destination, the Arab Baths. I had already passed them going to the Civil War bomb shelters I wrote about here. The baths demonstrate the mix of cultures and the construction of one on top another. The Moors built the underground public baths, hammam, in 1002 at the site of the baths that the Jewish community had constructed during the prior century. They were known as the Hammam Ibn Ishaq, the baths of Ben Isaac. The Jews had erected theirs on top of Roman wash sites. At the end of the 16th century, Spanish noblemen and administrators had the Arab bathhouse torn down and used the rubble to fill in the foundation of the Palace of Villardompardo, which stands over them now.

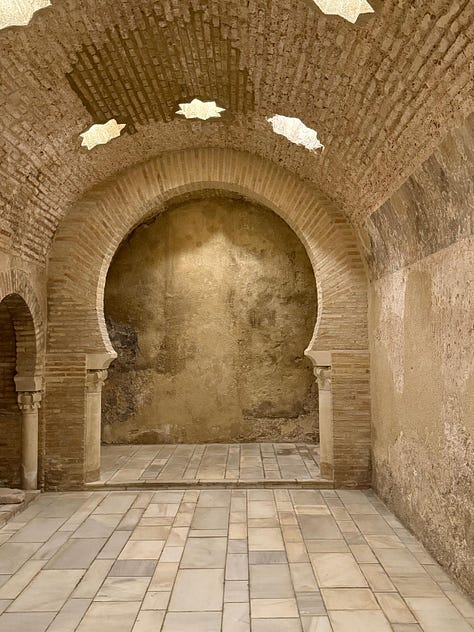

I descended the stairs to face the former hot, lukewarm, and cold baths as well as the changing rooms. Muslims believed water symbolized purity and used it to cleanse their bodies before praying. Christians found frequent bathing decadent and heathen so, to eliminate this practice, they destroyed most of the hammams in Andalucia. The baths in Jaén escaped this fate and were the largest in the region.

Brick arches supported the marble lobby and had allowed steam to circulate through the vestibule; the cold, warm, and hot rooms branched off this. Boilers next to the hot room filtered the heat through a series of channels between the walls of the room. People of Jaén moved from bath to bath not only to wash but to converse with their neighbors and friends.

I’ll soak in the baths of a hammam on an upcoming writing retreat with two writer friends in Granada. In that city, the original bathhouses, now modernized, are open to the public to bask in the cleansing rituals. We’ll let the steam and warm water relax our minds before we move onto that next essay, chapter, or paragraph.

Leaving the baths, I bravely strayed from Google Maps when I stepped off the route to enter the courtyard replete with trees, flowers, and a fountain at the church of Santa Cruz. A synagogue stood here before it was destroyed in 1391 to construct the worship space for Catholics. Drawing on the Arabic influence that pervaded the region, the builders used a Moorish design for the coffered ceiling. The nearby Church of Saint Andrew shared a similar story. It was once a synagogue and then became a mosque. The Catholics turned it into a parish in the 13th century.

Not lost yet, I strolled to the entrance to the former Jewish quarter where a large menorah now stands in the middle of a plaza. It represents the Jews who had been expelled from Spain. The base contains an inscription in Spanish and Sephardic: the footprints of those who walked together will never be forgotten. In honor of Spanish families in the Sephardic Diaspora. The menorah was the first in Spain to be placed on a public street, not in a synagogue. I crossed a small bridge spanning over the remains of an ancient gate into the walled medieval city. This was the entrance to the Jewish quarter.

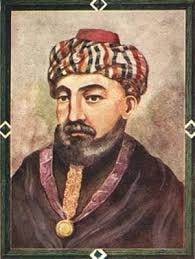

Blue and white ceramic street signs with Stars of David in the corners and the names of Catholic saints in the middle led me up steep, narrow cobblestone lanes. They took me to a small plaza where an oxidized sculpture of Hasday Ibn Shaprut, the head of the Jewish community until his death around 975, stood in the center. He served as doctor, minister of finance of the caliphate (the state under which religious Muslims lived), diplomat, translator, scientist, grammarian, and one of the faithful’s most trusted men. He became the head of all Jewish communities within the caliphate.

Centuries later, during the Inquisition which began in 1478, jurists and priests led tribunals, lay collaborators served as informants, and officials worked with family members rooted out Jews, conversos, and moriscos (converts from Judaism and Islam to Christianity). The faithful faced murder, forced conversion, or escape to other areas of the kingdom. In 1493, Jaén became the third city in Spain in which Jews, conversos, and moriscos were expelled from the country.

Perhaps other tributes to Jaén’s Jewish and Muslim history exist but I didn’t see them. The city has had centuries to build over these former communities. The reigning religion built sacred spaces on top of another, using the structure or materials of the culture before to save money, not as a tribute to another group. Jaén has tried, as many other cities have done, to uncover the past people and cultures and make them visible and better understood to us in the present. Maybe moving forward and before wiping out a people and their spaces someone will think about preserving or reusing their remains for reasons greater than saving money.

Thanks for sharing your tour of the underground places you visited in Jaén. I find it fascinating how many cities build themselves, and then get rebuilt over many decades and centuries later. It makes sense, but it is still so interesting. And what a reflection of the social and political mores of each time. But you are right to highlight the fact that more wasn't done to preserve some of the previous culture.

When we lived in Lyon, it was the first city I knew that just kept expanding outward instead of on top of the previous residents. So all the various cultures and migrations are represented still in the expanding circumference of the city, starting with the romans and moving forward in time. So interesting these older cities, aren't they?

Andrea, this is such a fascinating story. Your photography provides beautiful color and embellishment to your written description. Thanks, as always, for the tour and wonderful history lesson.