When my tour guide in the city of Jaén inserted a key to unlock a metal door leading to an underground passageway, I had no idea she was enclosing us in a bomb shelter. Only the sign above the entrance let me know our destination. She had undoubtedly told our group, but I’d missed about 70 percent of what she said because of her heavy accent of the Andalucian region. Additionally, she crammed thousands of facts into her spiel, so she never slowed down to give me time to digest them. Since we had just spent an hour in the Cathedral of Jaén looking at religion, I figured she wasn’t going to lock us in there. This bunker had housed up to 1,040 people crowded along cement benches while Franco’s Nationalist Party bombed this Republican city during Spain’s 1936 – 1939 Civil War. This refuge might have been just as sacred to the townspeople as the cathedral when they prayed for their lives.

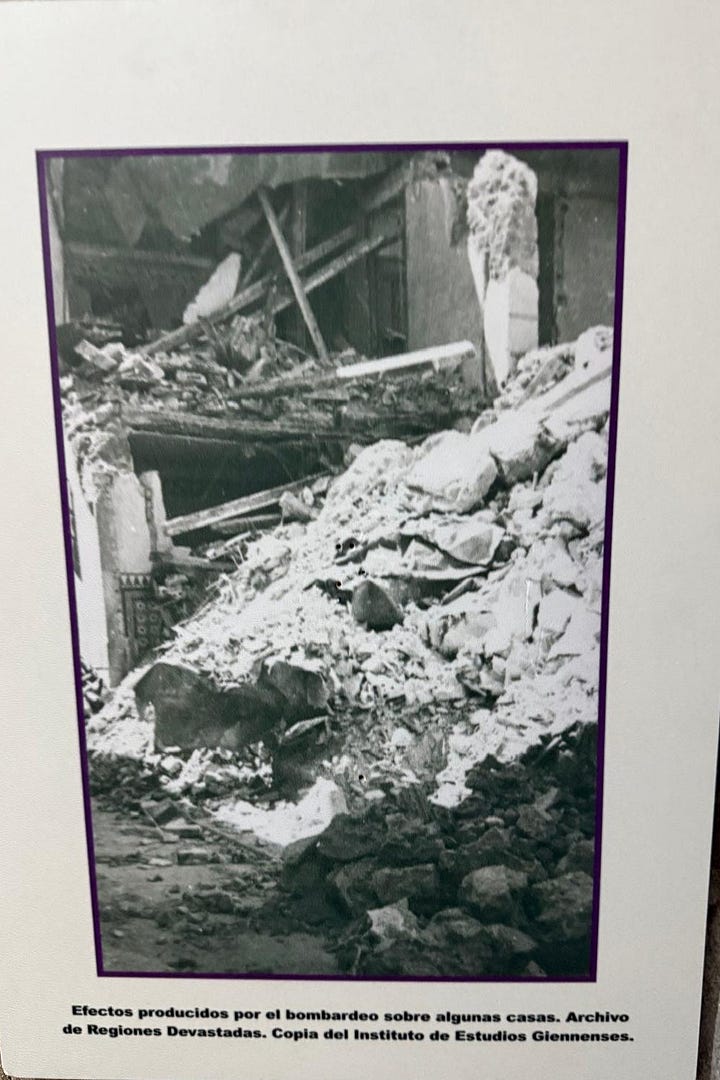

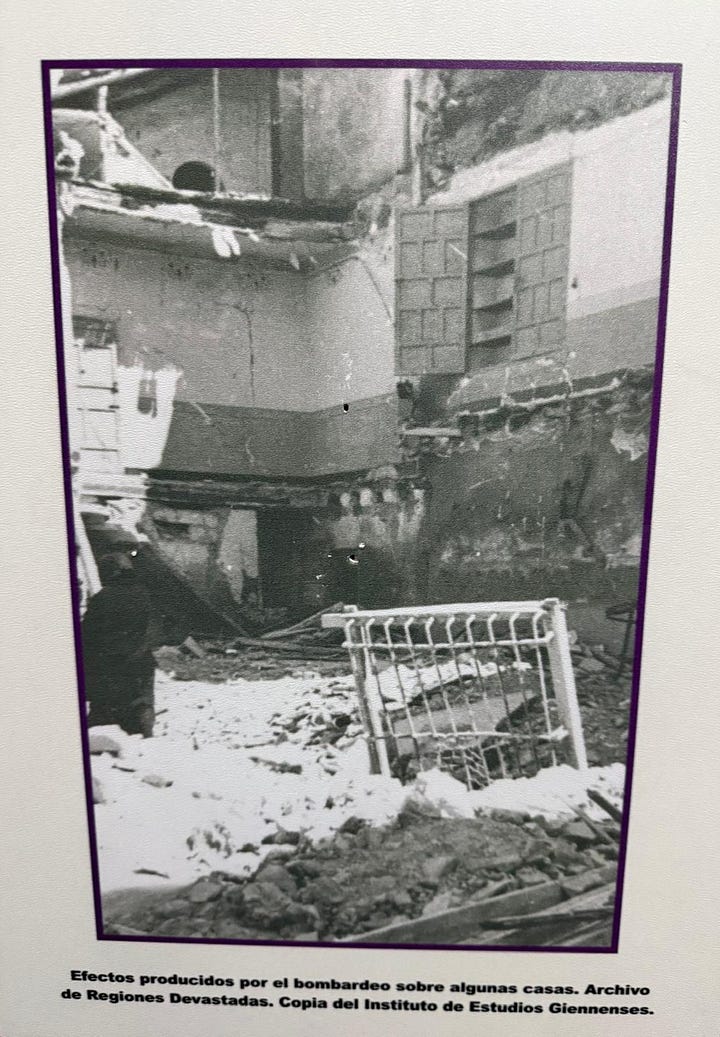

On April 1, 1937 at 5:22 in the afternoon, Spanish pilots in six bombers and in an escort of nine fighter planes on loan to the Franco regime from the Nazis swooped over the southern end of the city to unload seventy-five German and Italian bombs on homes, streets, markets, churches, and shops. At this hour, children had left school for the day and played in the streets or accompanied their mothers to buy bread, meat, cheese, and coal, or whatever the household needed. The bombing killed 157 people, mostly women and children. It wounded 280 more.

The bombing took citizens by surprise. Jaén was not a strategic site for the war, nor did it have troops, barracks, or ammunition storage sites. It had no anti-aircraft capacity, sirens, or shelters. After the attack, the city government drew up in five days a plan to build bomb shelters. By the end of the war, they had built 35 of them to accommodate a total of 8,800 people plus 144 smaller ones in homes, shops, and factories. Some were made of cement while others were dirt. The bombing of Guernica, another Spanish city, by the Fascists Franco, Hitler, and Mussolini, which I wrote about here, took place four weeks later.

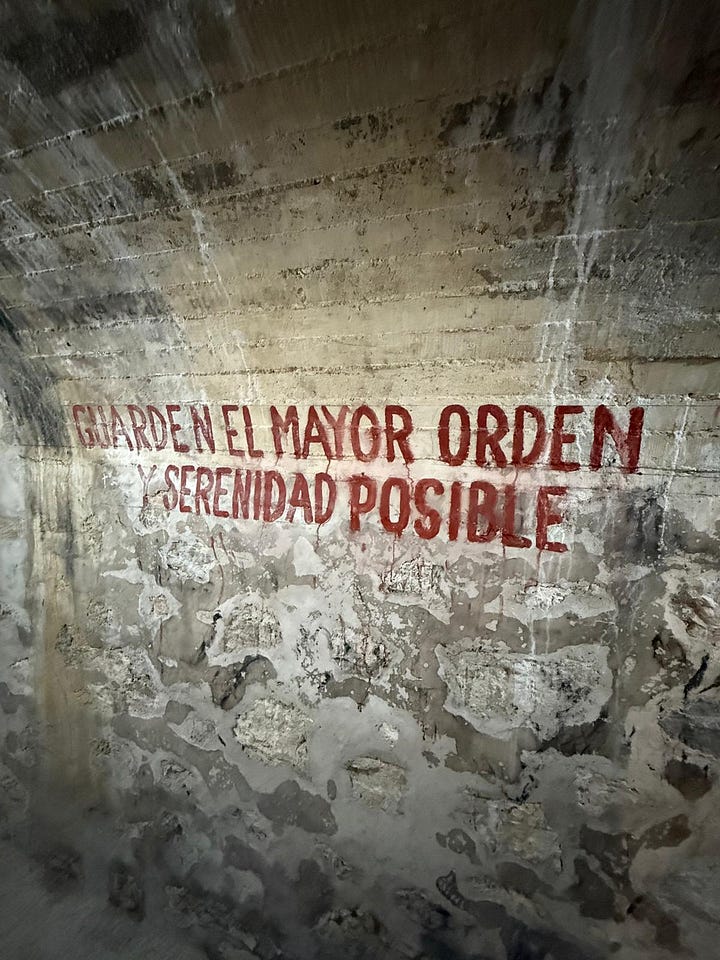

We tourists walked up and down the three passageways of the shelter, the Refugio Antiaéreo de Santiago. I could stand without hitting my head but those a few inches taller would have needed to stoop. At full capacity, the knees of those hiding would have rubbed against those on the opposite bench. Air circulating through vents brought in fresh air and sent out smells of sweat and dirt from the olive groves. During the war when the sirens sounded, people dashed to the shelters and piled through the doors. There they waited until they heard the all-clear signal. Amidst children crying and adults pacing, a sign reminded people to be orderly.

The city government constructed this shelter using material from the crypts and remains of the medieval Church of Santiago which had been in disrepair on this site since the mid-1800s. Before that, the Moors had attended mosque on this same piece of land. A rabbi’s home occupied the space before it was turned over to the Catholics during the Inquisition beginning in 1478. For centuries, the site of the bomb shelter had been a place of worship across religions.

The contrast between religion and war also arose during our tour of the Cathedral when we stopped in front of an ornately engraved gold and silver vessel that stood over three feet tall. Its elaborate design and symbolic power made us gasp. Until 1936, the men of the church paraded this sacred item finished in 1535 through the streets on holy days. Believers lining the roads worshiped the blessed host it contained. During the first year of the Civil War, Franco, despite being a devout Catholic, demanded this custodia procesional be melted to fund the Nationalists surge to power. What we saw was a reproduction made in 1986.

The day before the guided tour, I took a break from writing a book about my great grandfather, a prominent and controversial building contractor in Chicago at the turn of the 19th century (see here), to stroll around the city center on my own. I passed too many churches to count, a cathedral, the Arab baths built in 1002 on top of a Roman bath, shops, small plazas with trees laden with oranges, and the town hall. I came across Hospital San Juan de Diós built in the 15th century. I stepped into the remodeled building to admire the architecture and serenity of the Moorish-Spanish style courtyard.

I then headed across the way to a three-story stone building with windows occupying much of the façade. It housed a bright, spacious, modern youth hostel. Little did I know that underground lay another bomb shelter. The passageways in this one extended 525 feet with a height of over six feet. While digging the shelter, workers constructed an operating theater and because of its proximity to the hospital the only one in the shelters. The blue tiles demarcate the theater and the white ones the sterile area.

After the tour, I wandered around the city looking for the sites of other shelters but sidewalks, streets, buildings, parking lots, and plazas have covered them. Only these two remain open to the public. Most people who had heard the bombs whizzing through the air and took refuge there have died of old age. Although they lie underground out of sight, we walk on sacred ground. One doesn’t have to dig deep to remind ourselves of the days when Fascism and fear fell from the sky.

Timely and frightening observations with churches, authoritarians and bomb shelters interweaving in not so mysterious ways. Thank you for sharing your experience of the city on so many levels ❤️❤️❤️

Another great story from our recent history that should not be forgotten. Many thanks!