Sauntering down the trail of the northern route of the Camino de Santiago into the town of Zarautz, my husband Fabio and I confronted a sign that said “Tourists, remember: this is neither Spain, nor France. You are in the BASQUE COUNTRY.” We had just completed the first day of our hike in the summer of 2015 after starting in San Sebastian thirteen miles away. The next morning, readying to begin our second day, we entered a coffee shop to get breakfast. Nobody spoke Castilian Spanish. We couldn’t understand a word. Patrons ordered coffee, croissants, and juice in the Basque language, Euskera, the native tongue of the people living around the Spanish and French Pyrenees. We trekked for a few more days through Basque Country to the town of Guernica. I was engrossed in staring at my feet as I slogged along under the summer blaze to match the town with Pablo Picasso’s painting of the same name.

Fabio and I passed through Guernica, seventy-eight years after General Francisco Franco of Spain’s right-wing Nationalist Party had authorized the Nazi Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion and the Fascist Italian Aviazione Legionaria to carpet bomb the town. Germany’s ace pilot, Manfred von Richthofen, a.k.a. the “Red Baron,” wrote in his diary while the attack was being planned, “We are practically in charge of the entire business without any of the responsibility.”

For three hours on April 26, 1937, twenty-eight German and three Italian bombers dropped their payloads. Guernica, well behind the front lines of the Civil War, served as a strategic point in Basque Country to fight Franco’s troops. Republican soldiers used it as a communications center and as a place to prevent the Franco’s Nationalists from taking a larger and strategic city, Bilbao, in the north. These pilots practiced carpet bombing that they could use in a larger war to destroy civilians, buildings, bridges, and roads, and to scare Franco’s enemies in the region. That day, at least ten thousand residents, refugees, farmers, and people from Bilboa had flocked to the town center to exchange goods on market day. In addition to the bombing, about twenty-eight biplanes aimed their machine guns to strafe the people fleeing through the fields to herd them back to the locus of destruction.

These pilots carried out what a Spanish general said on July 19, 1936, the day after the military coup began, “It is necessary to spread terror…We have to create the impression of mastery, eliminating without scruples or hesitation all those who do not think as we do.”

The death toll at Guernica remains unknown but the Basque government estimated that 1,645 people were killed and 889 injured. Hundreds hiding in bomb shelters asphyxiated when the supply of oxygen ran out.

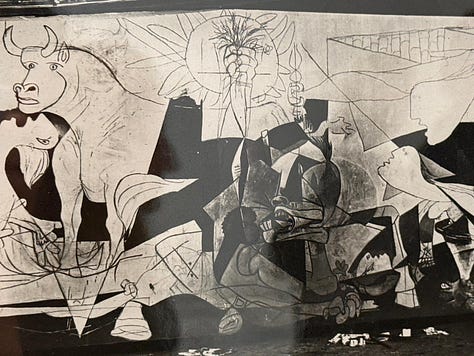

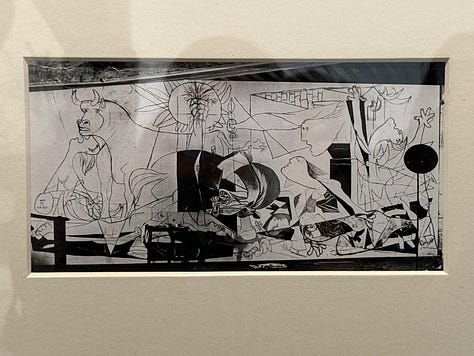

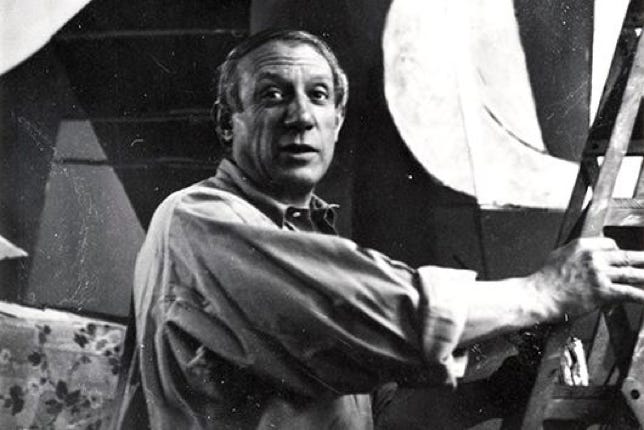

Picasso, who was living in Paris at the time, had been commissioned by Spain’s Republican government to paint a mural to display in the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition. For months, he struggled to come up with an idea. He made little mark on a canvas. Only when he read in the newspaper about the bombing of Guernica did he take his brushes to the unbleached muslin. He affixed a long-handled brush and hauled out a ladder to paint the corners of the canvas that towered over him. For two months he painted in black and white to suggest a documentary through a camera man’s eyes.

Guernica hadn’t appeared in my daily musings since Fabio and I had ambled through the town ten years ago until I took a guided tour of the highlights of Madrid’s Museum Reina Sofia where Picasso’ painting hangs. I stood in front of it two days after the inauguration of America’s forty-seventh president. As I pondered the 11.4′ X 25.4′ painting, our country’s new president had already signed on his first day in office twenty-six executive orders, including pardoning 1,500 individuals who had stormed the Capitol on January 6, 2021. Another order focused on “Protecting the American People Against Invasion” and others on defining gender and eliminating programs addressing diversity, equity, and inclusion. He also whipped his pen across the pages of twelve memoranda and four proclamations.

The display cases in the room where Guernica hung contained the correspondence regarding the masterpiece’s destination after the World’s Fair ended. Picasso in 1939 gave the painting to the Museum of Modern Art in New York stipulating that it not go back to Spain until the country returned to a democracy. In 1967, when Franco loosened some of the restrictions under his dictatorship, the government tried to get the painting back. Picasso denied this request saying it wouldn’t be transferred until Spaniards lived under a full democracy again.

When Franco died in 1975, two years after Picasso, Spain’s King Juan Carlos I initiated a democratic government. Still, Picasso’s heirs refused to give it up until 1981. After forty-two years in New York, a crew of handlers rolled up the canvas, packed it in a special crate, and secretly transferred it to a commercial Iberia Airlines flight. Baggage staff loaded it along with suitcases, bags, boxes, backpacks, and whatever else lay in the cargo hold. When the pilot touched down in Madrid, he announced Guernica was on board.

Our tour guide told us, as many sources confirm, that Picasso used Guernica to speak out about the horrors of war and the rise of fascist dictatorships in Europe―Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco. He wanted it to be a symbol of Spanish democracy and civil liberty. He used animals to represent human suffering, shapes to show chaos, and symbols such as a broken sword to suggest the futility of war. Because the painting’s shapes and figures are not specific to a time or place, it’s been used to depict the fight against the exploitation of human life and civil rights, the fight against tyranny and oppression, and other social and political messages.

News of the devastation of Guernica in English newspapers came two days after the bombing. Journalist and war correspondent for England’s The Times, George Steer, stated “Guernica was not a military objective...The object of the bombardment was seemingly the demoralisation of the civil population and the destruction of the cradle of the Basque race.”

I wedged my way into the middle of the crowd to get a closer look at the painting. No one spoke. Some didn’t budge for fifteen minutes. Probably that many people gather in front of Guernica at any given time each taking away the symbolism most relevant to them. My country of birth, the United States, hasn’t yet faced indiscriminate bombing of its citizens with weapons that kill but it is undergoing a blitz of words and actions that cause irreparable harm. They foster displacement, sickness, death, poverty, mental illness, and more in our country and around the world. What’s our Guernica to record, remember, and change this time in history?

whew. Indeed, Andrea, indeed. I hope our artists are working away now, more than ever. Thank you for this very illuminating essay tying the historical value and context of such important art to it's political context. And how we always need our artists to tell the truth.

Interesting background story. Thank you. Interesting fact about the Basque..... A Basque person is literally defined as someone who speaks Basque. Doesn't matter where you are from, if you can get by, you are one of them. That is why I love living here.