Gripping the steering wheel of a rented camper van to maneuver it through a voracious windstorm and the narrow, hilly streets of Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand, Fabio pulled the vehicle into the driveway of my dear friend from high school, Tim, and his wife, KC. Not only did we relax on comfortable couches munching on tortilla chips and salsa, we’d landed in an antipode, a point on the Earth’s surface directly opposite another point, connected by a line through the Earth’s center. If I had dug a hole from our living room in Madrid straight through the globe, I would have come up for air in Wellington in the land of kiwis: the fruit, bird, and people. Spain’s and that country’s capitals lie almost directly opposite each other. I didn’t expect to find anything from home in the furthest place from it I’d ever been, but those Spaniards got around. And kiwis traveled to them.

Tim and KC nourished us with homemade chili rellenos; a mesclun salad with garbanzo and black beans and tomatoes; and Hazy IPA. They provided a queen size bed, unlike our camper van in which we slept in a space resembling a CAT scan machine. A washing machine and dryer made us presentable again. The next day, they guided us around the capital’s famous attractions.

The influence of the Polynesians arriving in the 13th century, the development of the indigenous Māori culture, Dutch and British explorers coming in the 17th and 18th centuries, and Great Britain’s annexation of the country in 1840 underpinned nearly everything we saw. The Spaniards were not to be left behind though. Several scholars believe that Spanish galleons passed through this part of the Pacific in the 1500s and 1600s as they cruised the waters looking for treasures and territory for their king. Some have said a Spanish captain was the first European to see the country. Other historians believed that a Spanish vessel wrecked on the coastline. These explorers didn’t leave a trace or bring anything home that left a mark on either country’s history.

I took the historians’ words with a grain of salt during Fabio’s and travels through Te Ika-a-Māui/North Island. We took a ferry to a beach with an emerald sea and cream-colored sand where we saw no one sunbathing or strolling. We wound along a trail through a rainforest to a cove where a rock archway carved by wind and waves towered above us. We slid into the sea from a motorboat to snorkel amongst brilliant blue maomao so close we could touch them, sting rays, and sand daggers, among other species. Through our masks, we saw fish darting in and out of the seaweed waving below but no evidence of sunken galleons or treasure chests.

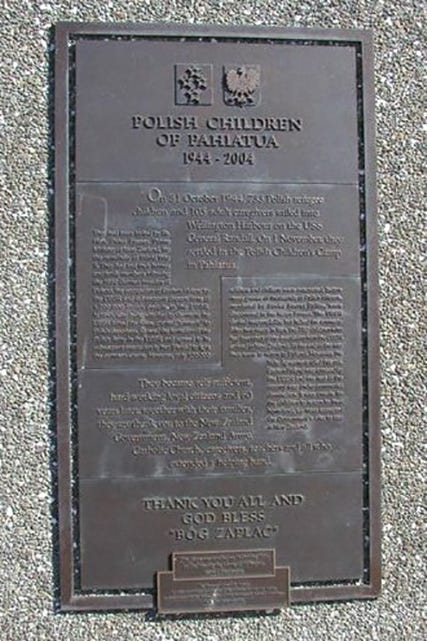

Touring the Wellington waterfront with Tim and KC, we ambled by statues, monuments, sculptures, museums, and historic buildings. We paused to read a bronze plaque commemorating 733 Polish children and 105 caregivers who in October 1944 had arrived in Wellington Harbor on a boat as refugees. They had lost their homes and families following Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939 and then Russian occupation. The New Zealand government offered them a safe haven. Later, they became citizens. There’s even a plaque on the wharf honoring Paddy the Wanderer, a dog cared for from 1928 until 1939 by waterside workers, seamen, and taxi drivers.

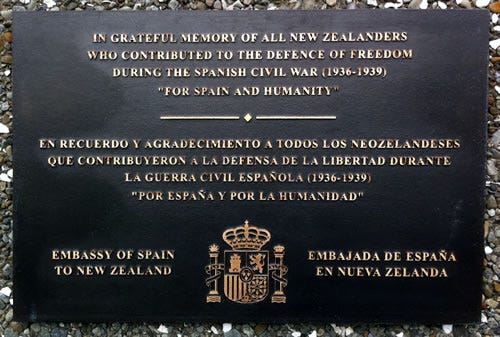

We missed, however, the only tie in the country between kiwis and Spaniards―a plaque to those New Zealanders who fought in the Spanish Civil War. In 2011, the Spanish ambassador to the country and Wellington’s mayor unveiled a bronze plate that read “In grateful memory of all New Zealanders who contributed to the defence of freedom in Spain (1936-1939) ‘For Spain and Humanity.’” This plaque was placed on the wharf, the workplace of some of the kiwi soldiers who had risked their lives for another country.

About twenty New Zealanders fought for the Republicans against General Francisco Franco’s Nationalist forces during the war. Though the country took a neutral stand following Britain’s lead, “where she didn’t go, we didn’t go,” those soldiers from around the world who fought in the International Column of anti-fascists held firm convictions as communists, trade unionists, and humanitarians that a democratic government in Spain was worth fighting for. Two kiwis in the International Brigade joined three thousand other soldiers marching into Madrid along its main avenue Gran Via on November 8, 1936, to oppose the Nationalists’ takeover of the city. Both died in the fight. In total, at least six New Zealanders lost their lives in the war. These would be the first of about 12,000 kiwis who were killed in the broadening fight against fascism during World War II.

Women New Zealanders also volunteered on the other side of the earth. The Spanish Medical Aid Committee (SMAC), the largest organization in Spain that raised funds to help war victims, the Communist Party, and various trade unions raised money through raffles, exhibitions, talks by war veterans, and film screenings. SMAC sponsored three kiwi nurses to come to Spain. They arrived in June 1937 after a month at sea and then traveled to a small town, Huete, in the central part of the country, to work in a slap dash put-together hospital in a monastery. The International Brigade ran the hospital.

One of the nurses transferred after a few months to the Pyrenees mountains and drove an ambulance. She got hit by shrapnel and had to return home. The other two stayed in Huete and worked forty-eight hour shifts providing anesthesia and keeping the instruments sterile, though they operated on plenty of patients with unsterile equipment after it became impossible to keep clean. When it was no longer safe to stay at the hospital, they and about a thousand other people, including members of the International Brigade, left in the dark of night for a three-day train trip to Barcelona, ducking the gunshots from Franco’s troops.

The two remaining kiwi SMAC nurses then traveled to a hospital in the foothills of the Pyrenees mountains with only a nightgown and a nursing uniform. When they washed the uniform, they worked in the nightgown. One said of her experience, “There is in everyone, hidden or otherwise, some spark of idealism… This was perhaps the reason I started nursing, and now, when I may put that knowledge to some real use in a land divided by civil war, which threatens democracy, I am proud that I should be one of those to help in unfortunate Spain.”

Other nurses came from New Zealand to Spain under their own steam. One joined the University Ambulance Unit which established a children’s hospital for refugees. This same volunteer then ran a children’s hospital under Quaker auspices in the city of Murcia. In 1939, she fled to France where she worked with the Quakers to set up refugee camps.

Several of the nurses on their return home continued to collaborate with SMAC to increase awareness of the plight of Spain. They raised money to buy medical supplies and provide care to refugees living in the camps in France.

All the while, the national tabloid Zealandia, founded by the Catholic bishop of Auckland, informed its readers that leftists and anarchists had attacked the Catholic church in Spain and had caused the war. The paper promoted Franco’s message that the town of Guernica (which I wrote about here) was bombed by communists and not German and Italian planes.

Tim and KC gave Fabio and me a different view of Zealandia. We drove up one of Wellington’s many hills to Zealandia Te Māra a Tāne, the world’s first fully-fenced urban ecosanctuary. It must also be the world’s only organization with a five-hundred-year vision: restoring the valley’s forest and freshwater ecosystems to its pre-human state. A fence surrounds the park’s circumference to prevent non-native species, particularly rats, mice, and stoats (similar to ermines) from feasting on birds like hihi, kākāriki, and takahē and the prehistoric reptile tuatara. Zealandia boasts forty species of native birds, twenty-four of them found in no other country. This Zealandia gave us another reason to appreciate the foresight of this country’s inhabitants.

People have lots of reasons to go to the ends of the earth: discover (and sometimes plunder) new worlds, escape persecution and war, enjoy the earth’s magnificent bounty of wildlife and wild places, connect with friends and family, and fight for what they believe in. Over centuries, these motivations haven’t changed and probably won’t. New Zealand, small as it is, sets an example about compassion and generosity at home and abroad.

Wow, I see I might have to write another post on the Kiwi - Spain connections :). I'm so glad you shared this information with me. Thank you. So much more than I imagined.

I see you live in Malaga. Is that correct? Jayne Marshall to whom you subscribe, another Substack writer, Sabrina Simpson who writes Geography of Home, and I will be in Malaga for a short time from May 2-3. If you're around and would like to have a drink or coffee, we'd be game.

I love the antipodes! I have to figure out where I’d be from Portland.