Snippets from Spain

Pádel Led Us to Poetry

I stumbled up the steep street cutting through Madrid’s Parque Oeste after friends Irene and Juan Ramón trounced us for two-hours playing pádel. Fabio and I had faced our first real match with real Spaniards. That didn’t lessen the sting. To recover from our loss and escape the sun’s fervor, we veered off the road into a small plaza. It welcomed us with stone benches shadowed by pine trees. I collapsed on a slab. Off to the side, a young man’s face centered in a bronze medallion gazed at me. I’d reclined at a monument dedicated to one of Spain’s most renowned poets, Miguel Hernández. The space’s serenity belied his death during the country’s Civil War while imprisoned for his anti-fascist activities.

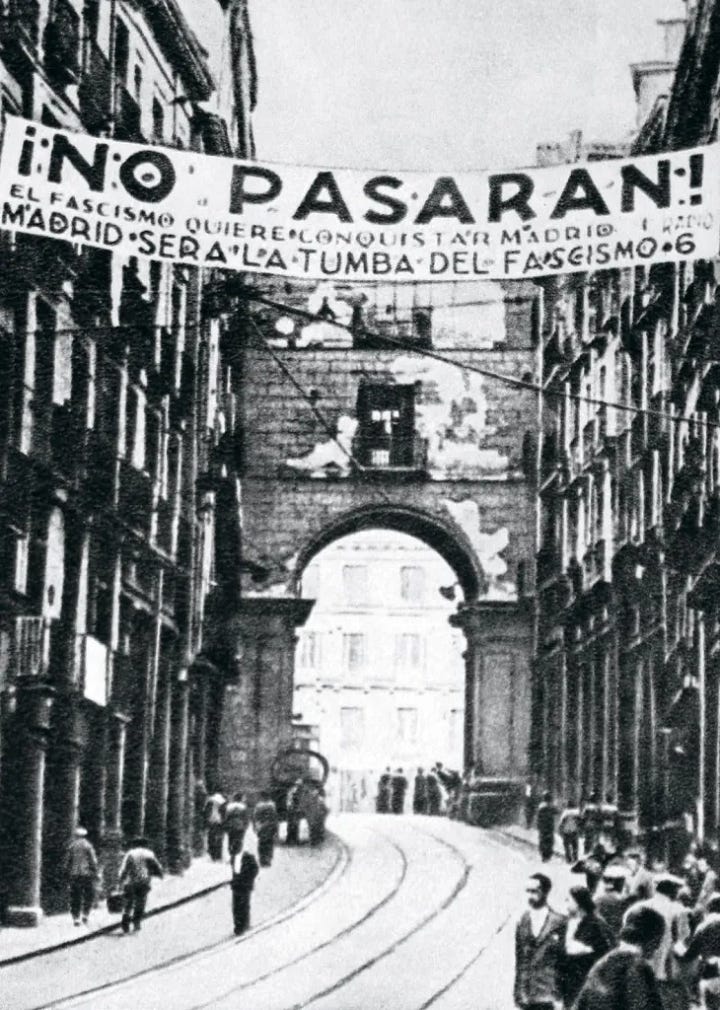

I’d never heard of him. Fabio knew exactly who he was. Fabio was seven-years old when Hernández’s poetry rose to fame in Latin America, including his home country Colombia. A Spanish singer-songwriter Joan Manuel Serrat made in 1969 an album of songs he had based on Hernández’s poetry. This record arrived in the region when military dictatorships beset Chile, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Nicaragua among others. The song “Para la libertad” resounded in every country. Protestors made it their fight song. It began with “Para la libertad sangro, lucho, pervivo” (For freedom, I bleed, fight, and survive). Here’s Serrat singing it in 1975.

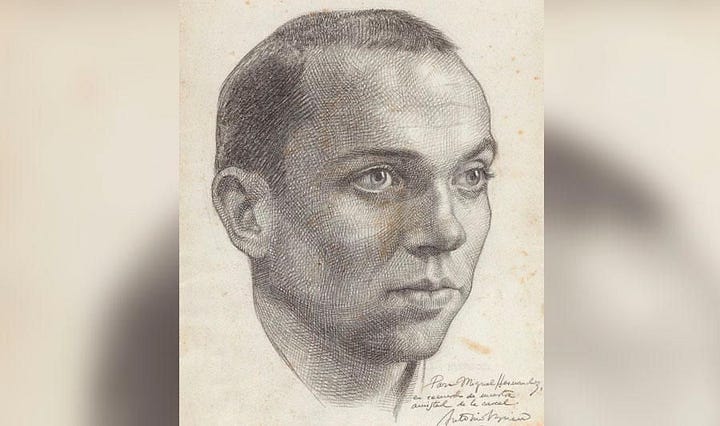

The rendering of Hernández’s face in the medallion came from a sketch that playwright and painter Antonio Buero Vallejo made of his friend when they were both condemned to death for opposing the fascist forces of Spain’s Generalissimo Francisco Franco. Hernández, sensing he would never see his one-year-old son again, asked Buero to do a pencil drawing of him to send to his wife.

Under the poet’s face lies an inscription with the date and place of Hernández’s birth―1910 in a town in the coastal city of Alicante―and his death in 1942 in a jail in that city. He was thirty-one.

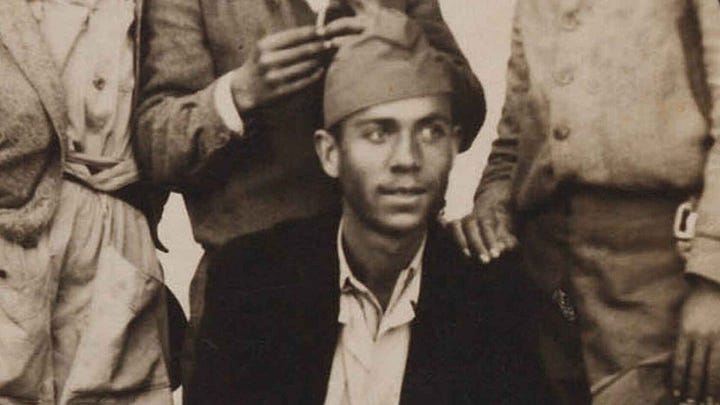

A boy who spent his childhood herding goats, working on a farm, and occasionally going to school became a published poet when he was twenty-three. He got involved with a group of Spanish writers concerned about workers’ rights. He became a member of the Communist party. He enlisted in the Republican army, where he spoke out for democracy, wrote poetry, and addressed troops on the front lines.

After the Republicans fell to Franco’s Nationalists, ruling party authorities arrested Hernández. When he stood trial in 1939, the judge sentenced him to death, saying he was “an extremely dangerous and despicable element to all good Spaniards.” Franco later commuted the punishment to thirty years in prison. He didn’t want the Republican figure to become a martyr like playwright and poet Federico Garcia Lorca, whom the Nationalist forces assassinated during the war.

In prison, Hernández wrote poetry, much of which he sent to his wife. He scrawled more verses on toilet paper. He described the horrors of the Civil War and his incarceration, the death of his first son the year before he went to jail, and the poverty his wife and infant son were suffering. These poems formed a book published after his death “Cancionero y romancero de ausencia,” “Songs and Ballads of Absence.” Many literary figures consider this some of the country’s finest twentieth century poetry.

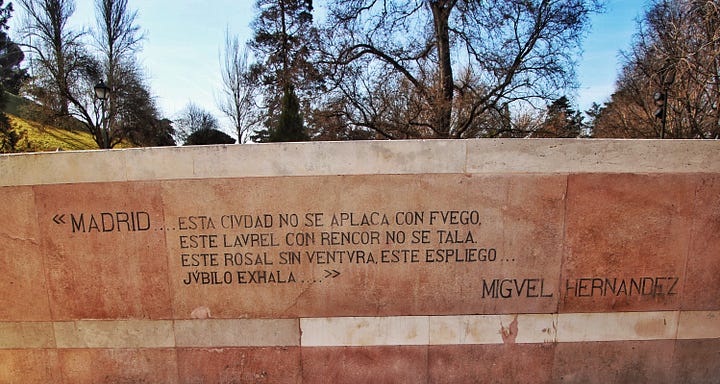

I got my first opportunity to read some of the poet’s words while resting on the stone bench. On one side of a curved wall, I saw his lines dedicated to Madrid: “This city is not pacified by fire / this laurel is not cut down out of spite / this unlucky rosebush, this lavender, exhales joy.”

While in jail, he scribed in verse a response to a letter he had received from his wife in which she told him that all she had to eat was bread and onions. The poem “Nanas de la cebolla,” “Onion Lullaby,” described his son breastfeeding on his mother’s blood tinged with onion. Hernández turned images of his wife into a symbol of desperation and hope for his broken country.

The government moved him from one prison to another. In them, he got sick with pneumonia, bronchitis, and finally typhus and tuberculosis, which in 1942 killed him. He scratched on the wall of the hospital, “Goodbye, brothers, comrades, friends: let me take my leave of the sun and the fields.”

After his death, his poem Para la libertad with Serrat’s music symbolized hope and resistance as Spain transitioned to democracy after Franco’s died in 1975.

Hernández’s family filed in 2010 a lawsuit in the Spanish Supreme Court to annul the death penalty and his crime of having leftist leanings. They asked the court to proclaim him innocent. They dug up new evidence in his defense, a 1939 letter from a fascist military official. Hernández “is a person with an impeccable past, generous sentiments and deep religious and humanist training” who showed “excessive sensitivity and poetic temperament.” “I do not believe that he is, at heart, an enemy of our Glorious Movement.”

Serrat said, “The relevance of Hernández’s verses remains, beyond the place and time in which they first appeared and their context, sounding as solid and fresh as if they had been written yesterday and right here.”

After that first pádel game, Irene and Juan Ramón whipped us two more times. They are still our friends. They did us a favor by forcing a rest stop where we learned about one of Spain’s most admired poets and what courageous people will sacrifice for freedom. Para la libertad rings true today. It’s time to translate it to English and belt it out.

What a beautiful soul and tragic story. Thank you for sharing this with us.

I love how you turn a random stop into an exploration into a fascinating individual! Maybe that is one of the special treats of living in Madrid, too, with its beautiful parks, statues and memorials. And what an amazing life he led and how inspiring to use his language to call out the injustices he saw and experienced. And how his poetry inspired others to continue to fight for justice. Very impressive! Thank you for providing an example for us in a time when we need to know about artist-fighters like Hernández.