Snippets from Spain

The U.S. Invited Basques to Immigrate: How Times Have Changed

After the first day of a road trip from Marin County, California to Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming, my father would pull the black Ford station wagon into the parking lot of a Basque restaurant in Winnemucca, Nevada. The first time we made the journey, I was eleven years old. The next trip, I was sixteen. Each time, a waiter sat us at a large wooden table with little space between patrons. My parents ordered platters of lamb, bowls of beans, and hunks of bread for the meal served family style. The notable thing about Americanized Basque food was my parents’ delight in taking us to a foreign restaurant. What these Basque people who had immigrated from the Spanish Pyrenees mountains experienced to survive and thrive there was less evident than the cuisine.

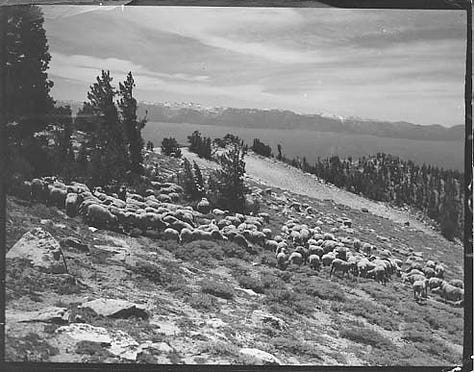

Continuing my parents’ tradition of touring the West, my husband, children, and I explored the High Desert Museum last week in Bend, Oregon. An exhibit about the Basque recalled those restaurant outings. This community offered more than mutton and had traveled farther than Winnemucca. Though they were farmers back home, the Basque in California, Nevada, Idaho, and Oregon beginning in the 1850s played a vital role in expanding the country’s sheep industry.

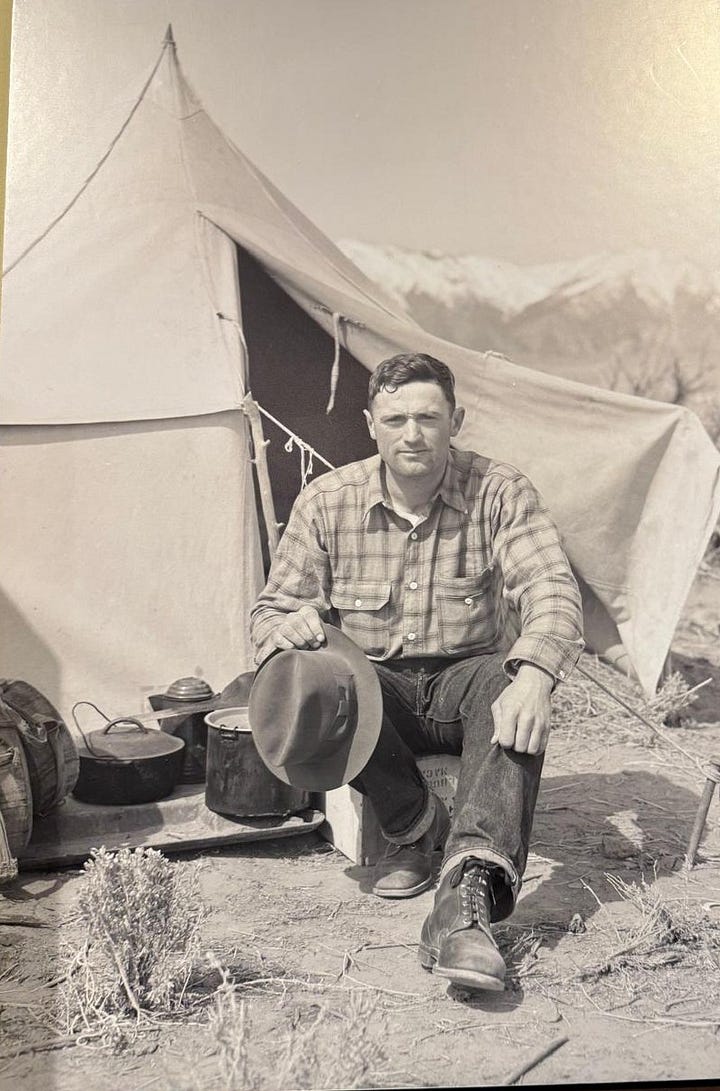

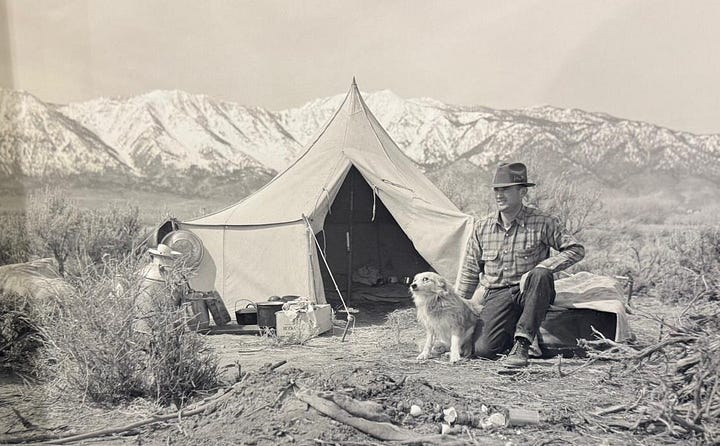

Basque men landed in California to dig for their fortunes in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains during the 1849 Gold Rush. Often the native-born miners’ anti-immigrant attitudes prevented foreigners from panning and mining, so these Euskaldunak (newcomers) turned to California’s sheep industry. As cattle ranching in the state expanded into sheep territory, these Spaniards moved to northeastern Nevada, southwestern Idaho, and southeastern Oregon―mountainous and habitable for these critters. The men took this solitary, isolating job that most Americans wouldn’t do.

The shepherds would descend from the upper pastures in the winter to stay, socialize, and eat in hotels and boarding houses, particularly in Winnemucca, Elko, Reno, and Ely, Nevada. Most spoke only their native language Euskara, which is the one surviving example of a pre-Indo-European language. It’s unrelated to any other.

The museum exhibit displayed shepherds’ tools: a knife, horn trimmers, a crook, and an emasculator. You can imagine what that did. A leather wallet had an embossed image of the jota, a traditional Spanish dance. Three years ago, while visiting friends Ivan and Eva in a village near Segovia, we watched their girls practice the steps for an annual festival, as their parents and grandparents also did at the same age. The scarves covering their daughters’ shoulders had been handed down four generations. Their grandmother had knitted their wool knee socks.

As the shepherds gained experience and money, they began to own flocks and land. They brought their families. Wives cleaned the boarding houses. In time, some became proprietors. They translated documents and resolved banking and medical matters as the newcomers adjusted to their new country.

The Basque experienced a slowdown in immigration in the 1920s. The western states passed legislation to create national forests and make land open to the public. Strict immigration laws controlled the arrival of foreigners. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 regulated the use of public lands to protect them and prevent erosion. This legislation reduced the shepherds’ ranges and flock size. The Depression struck.

With the beginning of World War II, things began to look up for them in an ironic turn of events. To ease the labor shortage in the sheep industry, Nevada Senator Pat McCarran, a fierce anti-communist Democrat and buddy of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, advocated in 1949 for “Sheepherder Laws” that gave residency to Basque shepherds. McCarran, a rancher himself, came from a state of 140,000 people where sheep outnumbered humans. His first bill welcomed forty-eight Basque shepherds. He wanted more.

With Franco’s help, McCarran opened an immigration office in the Basque city of Bilbao to expedite the new Amerikanuak (American Basques). He encouraged the State Department to admit the annual quota of 250 in 1949 and 1953. He pushed legislation in 1954 for another 385, exceeding his own quota, because wool production was “essential to national security.”

This wasn’t just a good hearted attempt to revive the sheep industry in his state, Oregon, California, and Idaho. In language resonating with today’s government, he had said, “Today, as never before, untold millions are storming our gates for admission and those gates are cracking under the strain.” He railed against “militant communists, Sicilian bandits, and other criminals.” After World War II, McCarran, a colleague of Joseph McCarthy, prided himself on his anti-communist crusade and his vigilance rooting out sympathizers. However, he went out of his way to allow an increased number of Basque shepherds from a country ruled by a fascist to live in his state. If called on this practice, he said, “Communism is worse than fascism.” His chummy relations with Franco ensured the flow of Basque shepherds to Nevada’s ranchers. “I am nothing without serving Nevadans,” he said.

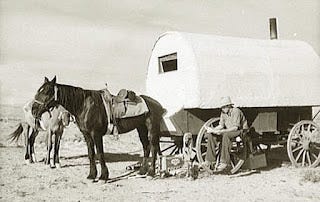

According to writer and historian Vince J. Juaristi, “No other group of immigrants enjoyed such preferential treatment, or expeditious attention. If a Basque sheepherder in the Pyrenees applied for a visa … within a month he found himself with a dog at his side and a willow in his hand herding a band of 1,000 sheep in Nevada or another western state, sleeping by a campfire, and eating beans from a can.”

By 1954, McCarran’s bill had brought in 1,135 Basque because of their special shepherding skill, favoring them over other immigrants. His actions delighted Franco so much that the dictator awarded him with the Grand Cross of the Isabel La Católica, an award foreigners rarely received.

By the time my parents introduced their children to Basque meals in Winnemucca, shepherds and their families had long integrated into American society. They had bolstered the nation’s sheep industry, doing physically demanding, lonely work no one else wanted. Though these immigrants were “invited,” they came for the same reason most do: a better life and new opportunities for their families. Like many newcomers, they’ve helped create a diverse and prosperous America.

I’d love it if you subscribed to my other Substack post “Building Modern Chicago”

Victor Falkenau’s life and legacy offer a window into the rise of a great metropolis. His story showed what it meant to rebuild Chicago after the 1871 fire and raise a family in a city that over a century ago represented everything America could be.

Wow. I knew nothing about the Basque in the American west. We like immigrants when it’s convenient for us. In their favor, the Basque were not Brown— although we invited a lot of Mexicans to be farm workers (“braceros”) until we changed our minds …

I had no idea about this! On this, the saddest, most disgusting and disheartening 4th of July ever, it's an amazing thing to learn. Thank you - I'll pass it along to my father.